Chapter 1: Cleaning

I’m Miguel. And this story starts with shit. Literally. The good kind, accumulated over the years, the kind that sticks to the boots and to the soul. Because Mastorrencito, you know, has its rural charm and its weight in history, but it also keeps secrets under dust, mud and oblivion. What I didn’t know is that, when I finally decided to clean out the barn, I was going to unearth something that would change everything.

Mastorrencito has the main house, of course. That’s where we live. But he also has two outbuildings that have always intrigued me: the barn, and that other kind of giant hut, with an architecture that gives a thousand turns to any magazine chalet. With its central column, majestic, in the middle of nowhere, as if to say: “I endured wars, storms and oblivion. What about you?”

Since I arrived here, many years ago, I always wanted to reform them. But renovation costs money. And here, between roof repairs, dogs, life itself… money always goes where it’s tightest. I calculate about 80,000 euros per space. So I left them. And they, like everything that is left behind, began to rot. Broken windows, damp to the marrow, beams eaten away by time. But that column was still there, planted like a sentinel.

Until one day, not long ago, I said: enough. If I can’t reform them, at least I’m going to empty them. Clean them. Take out everything that was left over. Because it was already embarrassing. A giant storage room of things I didn’t even know I had. And besides, every time I walked past it, I felt a kind of tug, as if the place was asking me to look at it again.

I set up a crew. Good kids. One of them, Javi, told me that his grandfather had worked in Mastorrencito during the postwar period. That he had once heard about “strange things” stored in the barn. I laughed at the time. Now it’s not so funny anymore.

We entered the spaces like someone entering an ancient womb, with respect but with brooms, wheelbarrows, gloves and masks. We took out broken sofas, bicycles without wheels, sacks of petrified cement, empty paint cans, an armchair half eaten by rats, an absurd collection of glass jars with colored liquids that I didn’t even dare to open. We sorted as in a ritual: this is pure garbage, to the container; this I have no idea, intermediate pile; this can be sold, for my gypsies.

While they came and went to the junk shop, I was rummaging through the objects I didn’t understand. A couple of times, Masto wandered into the piles, sniffing curiously. Mamas barked as if to say “watch out!”, while Maqui and Mato played chase each other through the rubble. Their energy gave me a little hope. As if they, with their instinct, knew something was uncovering.

We found, among broken boxes and boards, an oil portrait. Covered with dust. We cleaned it carefully. It was the face of a serious man, with piercing eyes, an old medal on his lapel and a background I recognized immediately: the facade of Mastorrencito, but with a shield that is no longer there. I left it leaning against the wall. I didn’t know what to do with it. I didn’t even know who he was. But his gaze, I swear to God, seemed to follow me.

The first construction we emptied was that of the column. Little by little, the floor became visible. And then it happened. After sweeping for hours, and removing layers of hardened soil, we saw tiles appear. Not just any tiles. They were terracotta, like those in the main house, but many had a mark that left us frozen: four bars and a date.

I knelt down. I ran my hand over one of them. It was perfectly preserved. The red clay had a shine that seemed impossible after so many years hidden. It was as if time had passed over them without daring to touch them. As if something, or someone, had protected them.

That night, I didn’t sleep well. I kept thinking. 1714. Not just any year. The War of Succession. The fall of Barcelona. A before and after in the history of Catalonia. Why were those tiles there, hidden, as if waiting to be discovered? Who put them there? Why?

The next morning, I went back to the barn with the dogs. Mastitwo was ahead of me, as usual. Mamas was beside me, serious. Maqui and Mato, playing at biting each other’s ears. We entered the building. The light came in through the high windows and the dust floated like in an old movie. There were the tiles, shining as if they wanted to tell me something.

And they did.

Right in the center of the floor, under the column, was a slightly more sunken tile. I bent down. I touched the edges. It was loose.

I lifted it.

Underneath there was no earth. There was a hole. A square of about 60 by 60 centimeters, perfectly delimited by old bricks. Inside, a box. Black wood, old, with rusted but intact hardware. It weighed little. I took it out carefully. The dogs approached, restless. Mamas growled. Maqui stood still, her gaze fixed. Even Mato sat down, which was rare for him.

I didn’t open it. Not yet. I sat with the box on my legs, heart pumping hard. I felt that what was inside wasn’t just old. It was important. Like I’d been waiting for that moment for centuries.

Chapter 2: The box

The box weighed less than it looked. It had that texture of old wood that almost creaks under your fingers when you touch it, as if protesting at being disturbed. I sat on a block of stone while the dogs clustered around me, expectant.

With the small knife I always carry in my pocket, I carefully forced the latch. The metallic creak echoed throughout the barn like a dry gunshot. Masto gasped. Maqui jumped and took two steps away, but stood watching. I opened the lid slowly, as if I were unearthing an ancient promise.

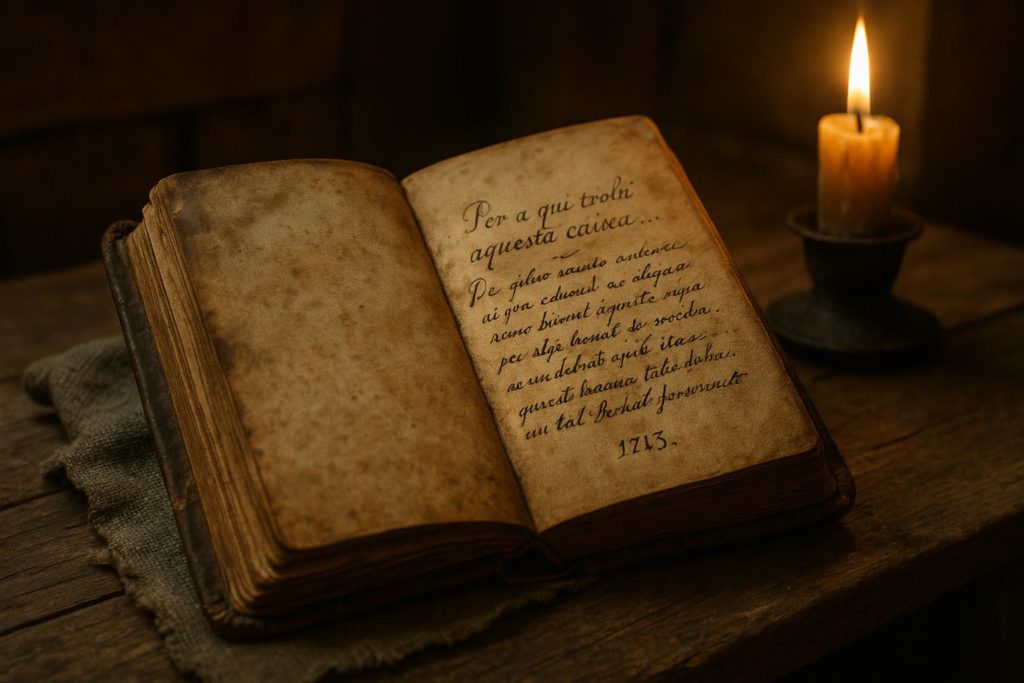

Inside, the first thing I saw was a package wrapped in cloth. Thick, gray cloth, with frayed embroidery. I unwrapped it and a book appeared. Small, dark leather, no title in sight. I opened it.

It was a diary.

The first page was handwritten, in faded ink, in old Catalan, beautiful and somewhat difficult to understand. “Per a qui trobi aquesta caixa…” it read. From there began the story of one Bernat Jorba, dated 1713. Soldier. Refugee. Hidden in Mastorrencito.

I could not believe it. The diary spoke of the war, of how they hid in houses scattered around the area, of a network of messengers and of an object they had to protect at all costs. “El cor de la terra”, it called it. He never explained what it was, but he did explain where it was: under the column.

I looked up at the column. I stood up. So did the dogs. It was as if they knew. As if all those years hanging around had been part of something bigger.

I went back to the hole. I took a closer look. In one corner, almost fused with the bricks, was a carved symbol. Four bars. Above it, a small keyhole.

The box had a double lid. Underneath the diary, a small rusty key rested wrapped in a red ribbon.

I took it. It fit.

I turned.

The ground shook. Not like an earthquake. As if something, inside the earth, responded to that key.

The dogs started barking all at once. Mamas, especially, started scratching at the floor near the column as if she knew exactly where. The brick creaked. An entire slab began to move.

And then I knew that what I had discovered was not just a diary. Nor a box. It was an entrance. To something much bigger.

But that… that I’m still not sure if I should have opened it.

Chapter 3: The passageway

The slab shifted with a thud, as if someone was pushing it from the inside. The dust that rose was thick, almost untouchable, as if it hadn’t moved in centuries. I froze for a few seconds. Masto was barking insistently. Mamas growled low, with that tension she only brings out when something really doesn’t sit right. Maqui and Mato stood behind me, restless, but not moving.

Under the slab, a dark hole. It was not very deep, barely a meter, but deep enough to reveal a stone floor and, beyond it, a tunnel that was lost in the blackness. It didn’t smell musty. It smelled… closed. Of frozen time. Of old earth.

I looked for a flashlight. I had to run up to the house. I grabbed a headlamp, a small handheld one, and went down with a rope just in case. The dogs were waiting for me right where I had left them. No one had moved. Not a hair.

-Shall we go in or what? -I said, more out of fear than courage.

I unhooked the rope and let myself fall. As I touched the ground, I felt the coolness. It was a different climate down there. I crouched down so as not to hit my head. The passageway was no more than five feet high. It started in polished stone, like a small Roman vault, and continued, little by little, transforming into something more rustic, with walls of compacted earth.

I moved forward. Slowly. I didn’t want the dogs to come down yet. Every step was a crunch. The air was charged with something ancient. Not fear exactly. But yes… memory.

About ten meters ahead, the tunnel turned slightly. And there I saw it.

One door. Iron. Reinforced. With a symbol engraved in the center: the four bars. This time, crossed by a horizontal line that I had not seen before.

TO BE CONTINUED………..

_______

From MasTorrencito we wish you a good day and may your dogs be with you!!!!

—

If you want, you can see our vouchers for weekends, retirees vouchers, at an incredible price… go to www.mastorrencito.com or if you want you can read more history and anecdotes that have happened to us in MasTorrencito… Click here … https://casaruralconperrosgirona.com